Version: Apr 20, 1999

|

|

Version: Apr 20, 1999 |

|

This is an attempt to build a modern, electric cylinder player at negligible expense. It is intended to play the cylinders themselves, not for transcription work. Therefore ease of use is essential, and to some extent reproduction quality has had to be compromised, as you will see if comparing it to some of the other phonographs presented on this site. Ideally, it should also be possible to put it in a living room without making it look like a machine shop. I have very little experience in machine construction, and a very limited range of tools at hand, so the result is mediocre craftsmanship at best. But, as I have now found it working, I would like to introduce you to my player.

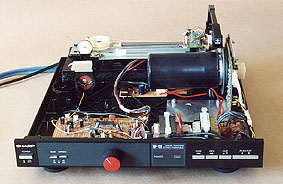

The basic concept is simple: a direct drive motor from one gramophone and a tangential arm from another. Decent gramophones can be had for almost nothing these days. In my case, the motor comes from a JVC L-F210 gramophone and the arm from a Sharp RP-111, but there must be many other suitable combinations. The whole assembly is built on the base plate of the Sharp gramophone, and fits under its original lid, even if the sides had to be raised some 55 mm. Outside dimensions are a relatively handy 165 mm high, 350 mm deep and 330 mm wide. The motor first had to be speeded up and given a regulator that covers the range of 120-160 rpm to be able to play different types of cylinders. When selecting the gramophone to provide the motor for a phonograph, one should look for one with a pitch control. This means you can change the speed over a very wide range with a variable resistor. To find out where to put it, search the circuit board for the existing pitch control resistor(s) and for the 33/45 rpm switch. The pitch control on my finished phonograph is the red knob on the front panel. Then the motor will have to be stood on end. I use an aluminium plate. The mandrel will have to be manufactured, for you will not find any suitable ones out there. I managed to talk a skilled craftsman into making one for me. It has to fit the motor shaft, it must be possible to put it on and take it off many times (you will need this while building your machine), and it must fit the cylinders. The real problem seems to be to make the cylinders fit. I provided my craftsman with an old Columbia phonograph mandrel to check against, and when measuring the one he made its shape is precise to within 0.1 mm. But the curious thing is that when different cylinders stop on the Columbia mandrel in more or less the same place, on my new mandrel they vary greatly in position. Some stop 20-30 mm before reaching the rotor plate, others strike the rotor plate without engaging against the surface of the mandrel.

| |

|

|

| Front view with the top removed. | Left view. |

|

The Sharp gramophone is intended for use only with one designated amplifier, which also provides the power to drive the motor. So I had to find out what kind of current and provide it. It turned out it works best with 12V DC, so I just put in a common battery eliminator. Then I had to change the cartridge to get one that will accept the proper styli. The most convenient choice seemed to be a Shure M75 series cartridge, which are abundant in this country, and for which the Expert Stylus Company in England makes styli of any kind you can imagine. The Sharp RP-111 being a simple gramophone, it does not readily accept any more weight on the tone arm, so I had to forget about interchangeable headshells and just glue a cartridge in place. To accomodate for the variation in position of the cylinders on the mandrel, the range of the arm's sideways movement had to be extended a bit. This was easily accomplished by extending one of the holes in the arm's guiding rod. These holes tell the motor when to start and stop. As the motor and tone arm are separate devices, both started simultaneously as I turned on the power. What I really wanted was for the mandrel to keep still until the arm started moving. This is the way the Sharp originally works: the turntable starts spinning when the arm begins to move. So I installed a relay, powered by the Sharp's motor power, that closes the drive motor circuit when the arm starts moving. The tone arm is maneuvered by the Sharp's original controls, to the right on the front panel. After putting the cylinder on the mandrel, the fast forward button is pushed, which starts the arm moving to the left and the mandrel spinning. At the start of the groove the arm is lowered with the cue button. The start button can almost never be used, for it lowers the tone arm at one determined distance from the rest position, and the cylinders always stop at different lengths of the mandrel. For the same reason, and because the groove does not always cover the same length of the cylinder, an automatic return function is useless. The playing is terminated by pressing the stop button, which stops the mandrel turning, lifts the tone arm and returns the arm to its rest position.

| |

|

|

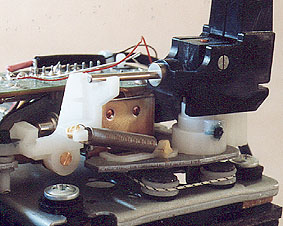

The lift mechanism of the Sharp RP-111 is not very strong and does not allow for much higher stylus pressure than that originally intended. The arm's drive mechanism, however, is very strong and rapid. |

In a cylinder player the starting position of the tone arm is towards the base of the mandrel, eliminating the risk of bending the stylus when putting on the cylinder. |

|

The phonograph in my living room, beside a common gramophone.

From the phonograph, the signal goes to a common preamplifier mounted directly behind the phonograph to avoid long cables. From there it goes on to an equaliser, a very useful device to make the sound from 78s and cylinders come to life, and then to the amplifier. At the start, I had some problems with 50 Hz hum, and installed separate grounding for all the sound equipment. It is in the form of a wire going to the living room radiator - not very orthodox, but it works. Christer Hamp, 1998 | |

| Any communication | ||