Version: Aug.7, 2002

|

|

Version: Aug.7, 2002 |

by James Nichols, 2002

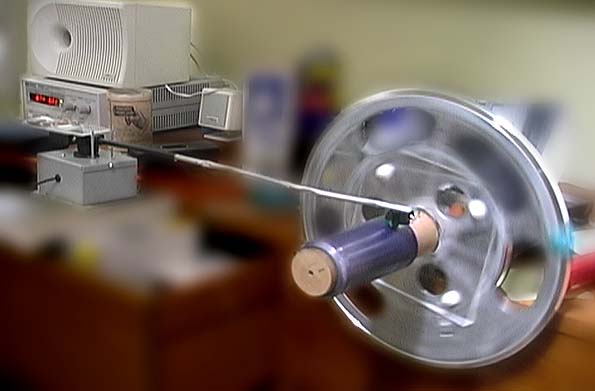

I first came across wax cylinders a few years ago while working as a volunteer at the Los Altos History House, a Silicon Valley (California) history museum. One day someone donated a large carton filled with cylinders, and the director Madelyn Crawford asked me if I could do anything with them. Edison was a boyhood hero of mine, but I'd never seen a cylinder up close, so I jumped at the chance. The collection included a dozen mysterious brown wax cylinders that were, judging from the writing on the lids, recorded at home almost a century ago. I was intrigued. An older gent brought in a lovingly restored Amberol player, but unfortunately, it was not calibrated to the groove pitch of the soft brown wax cylinders. We played a cylinder and it was totally destroyed. So I started to do some research. I soon came across Christer's pages, and was fascinated to see all these exotic reproducers being produced by craftspeople worldwide. Totally lacking in mechanical expertise, I began to wonder if it would in fact be possible with limited resources to transcribe these cylinders, many of which were in very poor shape. Since my professional background is in signal processing, I theorized that, given the crude nature of the cylinder recording process itself, one should be able to build an inexpensive reproducer and still get excellent results, since appropriate signal processing could conceal any limitations of the playback chain. Mulling over the problem and discussing alternative designs with friends, it became apparent that most everyone knew someone who had a stash of wax cylinders somewhere. The local museums, mostly staffed with volunteers, certainly did. I decided to develop a very basic mechanical reproducer whose design could be readily duplicated using commonly available surplus parts, with the hope that others could make quality cylinder transcriptions despite limited budgets or technical expertise. BURP-ONE (Basic Utility Record Player - Only Needs Electricity) was the result, and the cylinder transcriptions were successfully made. BURP-ONE was based on ideas gleaned from the "poor man's" section of the phono maker's pages. I wanted to build a machine using modern materials, for ease of duplication, but also as an expedient as I had no antique components. Total cost of materials was about $25. The platter, spindle, and motor assembly are from an 80's vintage belt-drive Sansui turntable. I literally ripped apart the plastic turntable chassis and extracted the motor, turntable, and tone-arm pivot (this was more work than I had imagined). I mounted the platter subassembly vertically on an aluminum chassis. The motor is driven by a precision variable DC power supply, which, together with the massive platter, gives good speed control. The tone arm was extended using aluminum tubing. The tone arm pivot is mounted on a small aluminum box. The additional mass of the tone-arm requires additional counterbalancing, which is provided by coins placed on double-sided adhesive foam (living in Paris, I prefer using the old 10-franc coins :-). Actually, the ability to precisely and quickly adjust the tracking weight proved to be a very useful feature, as I would frequently vary the tracking force, depending on cylinder condition, warpage, and stylus used. Perhaps the trickiest part was the mandrel. The original mandrel was made from a piece of acrylic tubing attached with epoxy to an acrylic base plate, which is attached to the aluminum platter using nylon screws. The acrylic tubing is lined with double-sided foam. A second layer on the inside nicely approximates the taper of a cylinder. The design has the advantage of being very gentle on cylinder. However, it was tricky to concentrically mount the mandrel assembly onto the platter. The crude design of the mandrel assembly introduced wow into the system, which was canceled by a counterweight (the green silicon putty) which can be seen in the photo above. Also note that the photo shows BURP-ONE with a wooden mandrel, which was precision turned for me by Don Louv; this mandrel works very well on later Edison cylinders. |

|

|

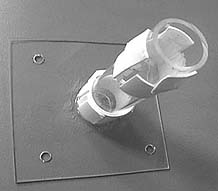

| The cartridge is reversed to read cylinders backwards, using the undamaged parts of the groove. | The original mandrel, made from a piece of acrylic tubing attached with epoxy to an acrylic base plate. |

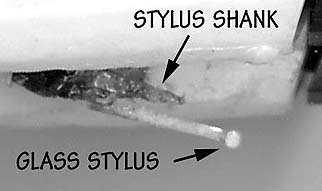

The cartridge used for most black-wax cylinders was a Shure M78-S with the standard stylus. For home-recorded brown wax cylinders, I used a home-blown glass bead stylus based on Henri Chamoux's recipe found on the phono makers' pages. These beads are quite tricky to assemble, but can give great results if the bead matches the groove geometry. I mounted the cartridge backwards and rotate the cylinder in the opposite direction of conventional playback. I've found that the lead-in grooves are often damaged and hard to track in the conventional rotational sense, but when approached from "behind", one can both more reliably start the transcription, and capture the important lead-in material. Others have suggested that this technique reads more of the undamaged ("downhill") groove information, which seems plausible. |

|

|

| The glass stylus, Chamoux style. |

Cartridge wiring for vertical readout. |

The PCM audio is captured using a 20-bit Sony DAT machine, running at 32,000 SPS, mono. The audio is subsequently transfered to the workstations using an optical path. Hum was minimized by connecting a wire between the tone arm assembly base and the pre-amp.The cartridge wiring is according to the diagram, which allows the cartridge to correctly transfer the vertical modulation (which would be noise in the lateral sense!). I use a variety of playback speeds when doing transcriptions. Very poor quality cylinders, especially those with a bad warp, are run as low as 20 rpm. For most pre-recorded cylinders in decent condition, however, I standardized on 58 rpm. This speed was chosen because it is logically half-speed when sampled at 32,000 and subsequently treated as 44,100. I usually subsample the PCM before processing to 22,050 sps, or 11,025 sps in some cases when experimental signal processing is performed. The speeds are calibrated to the voltage read-out on the precision DC power supply, which has shown to give excellent repeatability. In terms of transcriptions, I make the distinction between archiving and restoration. My work spans both fields, but I focus on the latter as the audio quality of a cylinder is often not acceptable to the modern ear, especially those who haven't been exposed to antique music. Further, achieving good audio compression without artifacts demands pre-processing to remove extraneous noise. Signal restoration in antique audio is a real challenge. Two of the most pressing problems are mold damage and warpage, which leads to obnoxious pitch variations. Mold patches are identified using wavelet analysis, and corrected using frequency-domain interpolation techniques. As for pitch variations, I developed a pitch correction system in MATLAB (based on ideas from Godsill and Rayner, and others) that worked quite well. This work was initiated after I had transfered a badly warped cylinder at the museum which subsequently shattered! I got rather carried away with this work and wrote a couple of papers for the Audio Engineering Society's 20th International Conference on Archiving, Restoration and New Methods of Recording that was held in Budapest last October. The first paper was on BURP-ONE, while the second was on a pitch correction system, which has also proven useful for materials such as stretched magnetic tape. The Nov. 2001 Journal of the AES, reviewing the conference, stated that BURP-ONE "...demonstrated impressive results using various methods of noise reduction." In summary, BURP-ONE was an experiment in developing a low-cost cylinder transcription unit that could be built without special tools or materials. The results have been encouraging, and I have transfered about 500 cylinders to date. I would like to up the budget a bit and develop BURP-TWO some day... |

| Write to James Nichols with comments or requests for transfers: | ||

|

|